A LIFE STORY like AN ARTIST’S NOVEL

The little that is known about the life of Carel Max Gerlach Anton Quaedvlieg (Valkenburg 1823 – Rome 1874), known simply as Charles, resembles a moralizing artist’s novel. It contains all the ingredients: an early-discovered talent; a journey to Rome; patronage from the Vatican; support from a princess; winner of “The Great Prize”; marriage to an Italian woman and permanent settlement in Rome. Then, a tragic twist of fate and an obscure death. It has all the elements of artistic romanticism – but what are the facts?

YOUTH AND EDUCATION

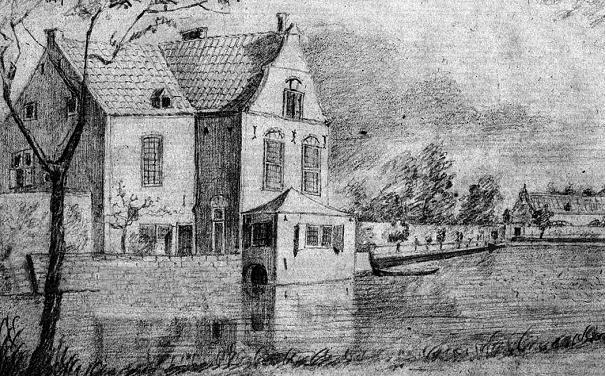

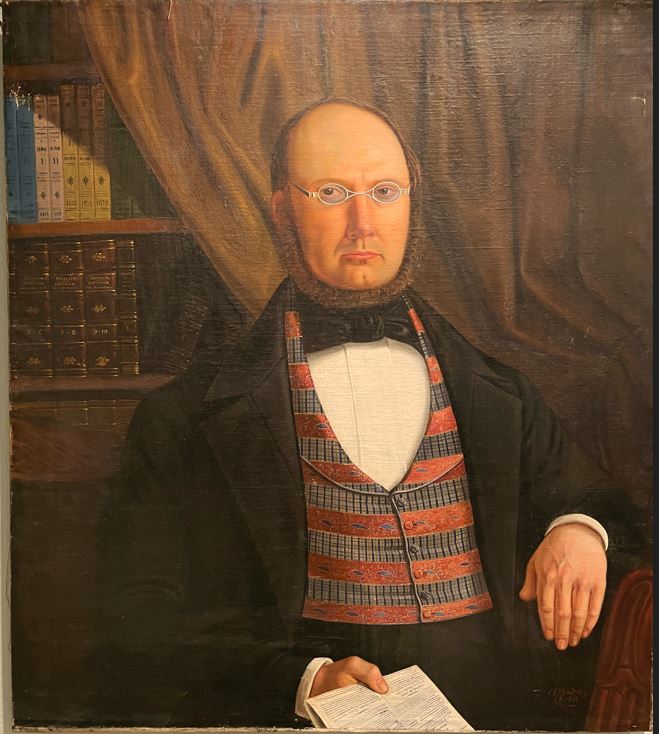

Charles was born the son of the mayor of Valkenburg. The Quaedvlieg family belonged to the local notables and was connected to the distinguished De Guasco family. The mayor’s family lived in an old fortified house called Palanka, located on what is now the Walramplein. Charles attended secondary school in Sittard, where his art teacher, the painter Lambert Hastenrath (1815–1882), taught him the first principles of drawing and painting.

According to old sources, he may then have gone on a Wanderschaft (journeyman’s travel) to further his skills in Düsseldorf, though there is no firm evidence of this. What is documented, however, is that in 1839, at the age of sixteen, he studied for one semester at the Antwerp Academy of Fine Arts, then directed by the history painter Gustave Wappers (1803–1874). From this period, two typical Biedermeier portraits have recently come to light, demonstrating his technical ability. In 1843 he returned there for another year of study. The reason for the interruption in his education remains unknown.

CHARLES QUAEDVLIEG — A LIMBURG PAINTER?

The assumption of a training period in Düsseldorf is repeated in the Biographie Nationale de Belgique (1905; vol. 18, pp. 398–399). The author, Jules Helbig, states that his brief biographical sketch was partly based on interviews with relatives. He clearly made an effort to preserve Quaedvlieg’s memory as a leading representative of the Flemish School. Unfortunately, his contribution remains the main source of information about the painter to this day.

It was not until 1963 that a local attempt was made to revive the memory of Quaedvlieg as a notable figure in Valkenburg’s history. This appeared in the journal Het Land van Valkenburg (14 June 1963), written by the priest Ad Welters under the pseudonym “Gerlach van Straebeeck.” His account contains a number of interesting facts, but also several fanciful anecdotes and inaccuracies.

More important than his birthplace or period of study, however, was his departure for—and permanent settlement in—Rome. There he is now regarded as a leading landscape painter, part of an international circle known as the “Painters of the Campagna.” More remarkably, every schoolchild in Italy knows his The Breach at Porta Pia (20 September 1870), depicting the decisive historical event that led to Italy’s unification as a nation. In 2020, an image of this painting was chosen for the first-day issue of a commemorative stamp series.

Why Rome?

t remains unknown why Charles decided to move to Rome permanently. As is often the case with such life choices, it was probably a combination of factors. The death of his 23-year-old wife in 1852 was likely the decisive reason for seeking a new life. Yet his social background, coupled with his religious conviction, undoubtedly also inclined him toward Rome.

In Limburg, there was as yet no fertile artistic climate. Although demand for religious art had increased since the restoration of the episcopal hierarchy in 1853, this development was still in its infancy. As a destination, Rome had already lost some of its appeal due to revolutionary movements that threatened the Pope’s temporal power—developments closely followed by Catholics in the Netherlands. (From 1860 onward, many young men even answered their priest’s call to enlist as Zouaves to defend the Vatican.)

Despite this unfavorable political climate, a study trip to “the Cradle of Art” was still highly valued by artists at home. A stay that lasted too long, however, was considered detrimental: one risked becoming estranged from national art and slipping socially into a half-dandy, half-bohemian existence.

LIFE AS A “GRAND SEIGNEUR”

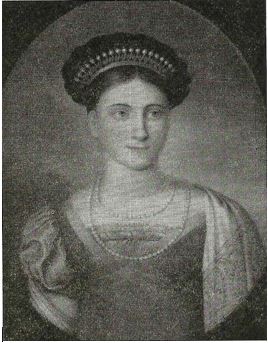

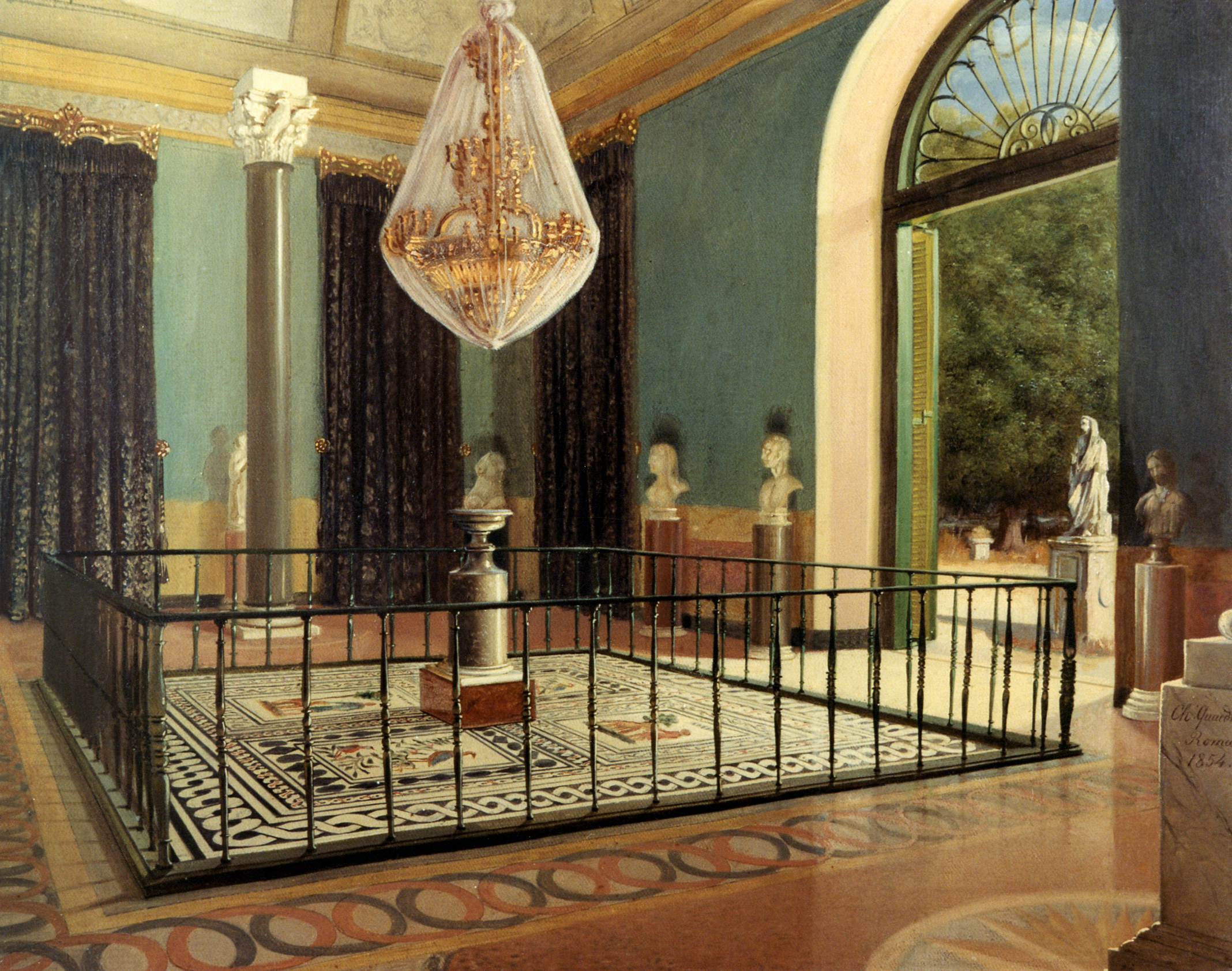

On 12–13 July 1853, Charles arrived by ship from Marseille at the papal port of Civitavecchia. He evidently soon came into contact with Princess Marianne of Orange-Nassau, who offered him seven months of hospitality at her Villa Celimontana (Villa Mattei). During this time Charles is said to have given her drawing lessons. From this period dates her pastel portrait by his hand.

His stay is also recalled by five interior scenes, which are exceptional within his oeuvre. They offer a glimpse of the vie de château he was able to enjoy for a few years. In 1854, he accompanied his patroness—together with a few fellow artists—on a journey to Ischia, an island off the coast of Naples. One of them was the future “society painter” Pierre Tetar van Elven (1828–1908). As a souvenir of her favorite retreat, the princess acquired two landscapes from Charles.

WANDERINGS THROUGH THE PAST

Charles spent about a year traveling through southern Italy, visiting Naples, Pompeii, and other historic sites. One of his companions may have been the British painter Robert Alexander Hillingford (1828–1904), suggested by the identical motif of a small boat in the Bay of Naples painted by both artists. This excursion to Naples and its surroundings clearly had the character of a sightseeing tour.

Charles described his travel impressions in a letter published in the Maastricht newspaper Le Courier de la Meuse—one of the rare occasions on which we hear his own voice. In short, he felt himself to be in the dreamed-of land of Arcadia.

Le Courier de la Meuse

“It is a great pleasure for me to stay in this delightful region where an everlasting spring reigns, where all seasons are beautiful, and where the entire year offers an unbroken cycle of new fruits and new flowers.”

STATIONS OF THE CROSS

It is likely that Charles Quaedvlieg felt a certain bond with compatriots who shared his faith. Unfortunately, no written evidence of this survives, yet the painting of Stations of the Cross can be seen as a connecting element. It is almost certain that Charles became acquainted at that time with two artists from the north who were working simultaneously on similar projects: Ludwig Brüls (1803–1882) and Carel Frans Philippeau (1825–1897).

Charles’s Stations of the Cross can still be found today in the parish church of St. Lambertus in the Limburg village of Nederweert. The series consists of fourteen stations with Neo-Gothic wooden frames, painted around 1855–1857 after examples by the Austrian painter Joseph von Führich (1800–1876). The exception is the Descent from the Cross, inspired by the well-known altarpiece by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) in Antwerp Cathedral.

WINNER OF “THE GREAT PRIZE”

An event in 1854 greatly enhanced the status of the Valkenburg-born painter in Rome: winning “The Great Prize” with a painting said to have been “placed in the Pantheon.” These oft-repeated words have caused some misunderstanding. Charles was not the winner of the Grand Prix for history painting awarded by the Accademia di San Luca, but rather of the old Roman Catholic artists’ association Congregazione dei Virtuosi al Pantheon. (This association had an exhibition hall attached to the famous church.)

The prescribed theme for painters that year was King Saul, and the subject of Charles’s winning entry was The Witch of Endor (1854). Princess Marianne purchased the work almost immediately. Unfortunately, neither the painting’s current location nor any reproduction of it is known today. The international artists’ community honored the winner with a torchlight procession and a laurel coronation on the Capitoline Hill.

All this recognition was of great importance to Charles. It opened doors that would otherwise have remained closed to him, such as those of international art academies.

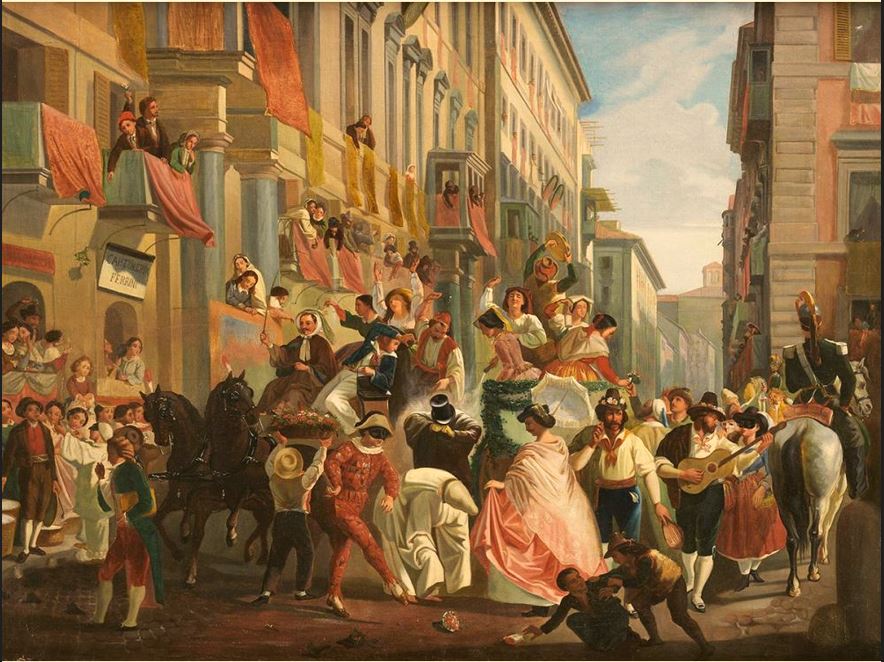

MASTER OF CEREMONIES AT THE ANNUAL ARTISTS’ FESTIVAL, 1 MAY 1856

In 1855, Quaedvlieg joined the Deutsche Künstlerverein (DKV, founded 1845). This was customary, as the Dutch colony in Rome was too small to sustain its own association. Robert Hillingford had been active since the society’s foundation; he had studied in Düsseldorf and was deeply involved in its social life. Together, the two painters produced a rather unusual work: The Artists’ Festival in Rome on 1 May 1856.

These so-called Cervaro festivals had been a long-standing tradition. They served as a kind of farewell celebration, for in summer most artists left the city, where the heat and malaria made life unpleasant and unhealthy. They would travel, usually in small groups, to one of the mountain villages around Rome.

The painting, much like Rembrandt’s Night Watch, is an informal group portrait featuring about forty miniature likenesses of artists. Identifying the costumed and mostly bearded gentlemen, however, is no easy task. It is known that the Swiss watercolorist Salomon Corrodi (1810–1892) acted as president, disguised as the god Jupiter, holding a starry scepter. Beside him stands a “poet” delivering a mock oration to welcome the gathering of some 300 artists. Naturally, the two painters also included themselves in the scene: Charles appears prominently, dressed as a red devil and seated on a white horse; Robert is shown in profile, wearing glasses and riding a donkey.

Quaedvlieg, serving that day as master of ceremonies, thus demonstrated the great esteem he enjoyed among his fellow members of the DKV after his prize-winning success.

KNIGHTED BY POPE PIUS IX

There is only one painting by Charles that matches the success of his previously mentioned prize-winning work: The Canonization of the Japanese Martyrs (1862). This painting depicts a significant ecclesiastical event that took place on 8 June 1862. It was one of Pope Pius IX’s (“Pio Nono”) initiatives to affirm the authority of the Catholic Church, as represented in his person. Bishops from around the world were invited to Rome to attend the canonization ceremony of the first 26 martyrs of Japan. From a high vantage point in the vast interior of St. Peter’s Basilica, the painting presents the Pope, cardinals, and numerous prominent guests.

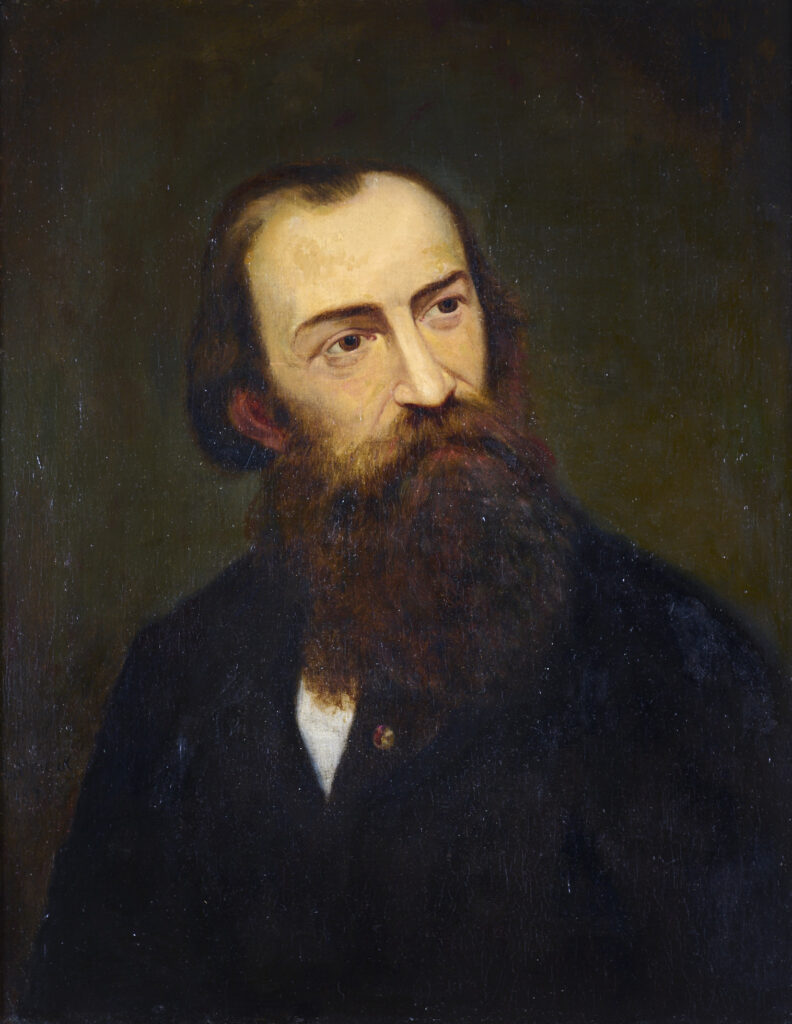

The painting was acquired almost immediately by the Pope, reportedly for a substantial sum. In addition, Charles was awarded the civil Order of St. Gregory, which granted him the title of Cavaliere. On a recently rediscovered self-portrait, this distinction is visible, worn in miniature on the buttonhole of his lapel. Such honors were extremely important for a 19th-century painter, significantly enhancing his social standing and opening the doors to elite salons.

A HIDDEN MARRIAGE

A significant event in Quaedvlieg’s life was his second marriage to an Italian woman. On 3 September 1856, he married the then twenty-year-old Maria Belli (1836–1896). Interestingly, this event seems to have been carefully omitted from both of the previously mentioned biographies. It was precisely the kind of step that moralizing literature warned against: artists, who were generally not wealthy, suddenly took on not just the role of breadwinner for a household, but often responsibility for an entire family. The Quaedvlieg family back in the Netherlands was likely not pleased either, as part of their—by no means insignificant—estate risked ending up in Italian hands.

The years 1856–1858 also marked a turning point in his artistic career. In 1857, Princess Marianne decided to leave the politically contentious city of Rome. She had her possessions transferred to her wine estate, Reinhartshausen, in Erbach, where she added a private museum as a wing. Seven paintings by Quaedvlieg found a place there.

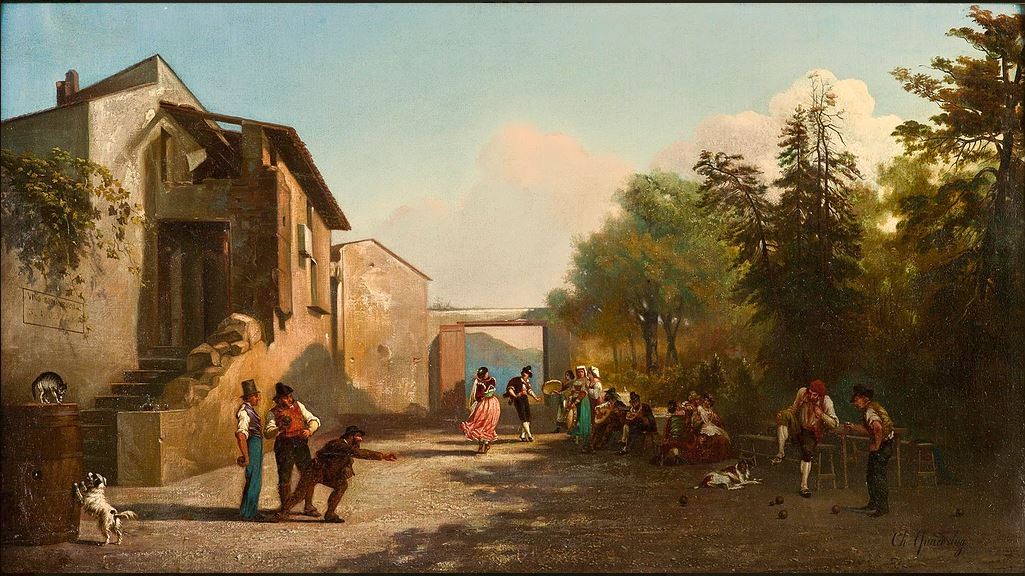

From 1859 onwards, Charles was no longer a member of the Deutsche Künstlerverein (DKV). To secure a stable income, he had to tap into a new market: that of Anglo-Saxon tourists. This increasingly included affluent Americans, who made winter pilgrimages to the “Mother of the Arts.”

PRAISED GENRE PAINTINGS

Despite an absence of nearly ten years, reviews of the Valkenburg-born artist’s work managed to reach Limburg through two prominent Roman newspapers, Giornale di Roma and L’Eptacordo. In 1860–61, Le Courier de la Meuse published two translated articles from the latter art and music journal. They stated:

“The name of Mr. Quaedvlieg resounds with honor in the fine arts […]. Raised in our [Italian] school and inspired by the works of our greatest masters, Charles Quaedvlieg already holds a distinguished place among the most renowned artists.”

These reviews followed exhibitions organized by La Società degli Amatori e Cultori delle Belle Arti, a society founded in 1829 to provide both Italian and foreign artists the opportunity to showcase their work.

The discussions mainly concerned two genre paintings depicting half-length portraits of young women; one of these features a woman dressed in the traditional attire of Albano, entitled The Cotton Picker.

Equally well-received was his depiction of the Roman Carnival (1860), a painting for which Charles submitted a more elaborate version to the exhibition the following year. He also exhibited landscapes with the Amatori e Cultori, one of which was favorably noted for its variety of animal figures.

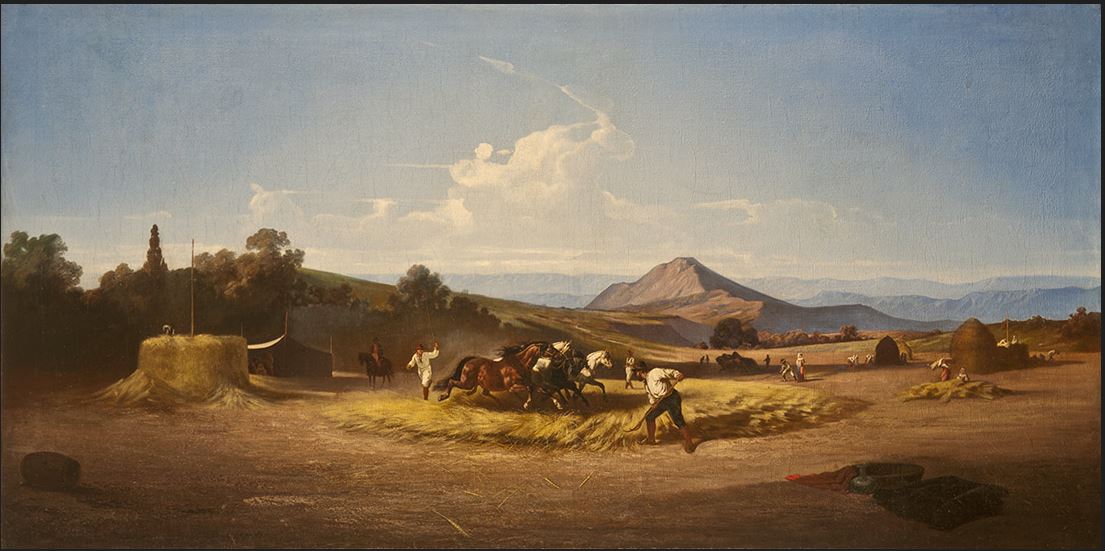

SEARCHING FOR NEW MOTIFS IN THE “CAMPAGNA”

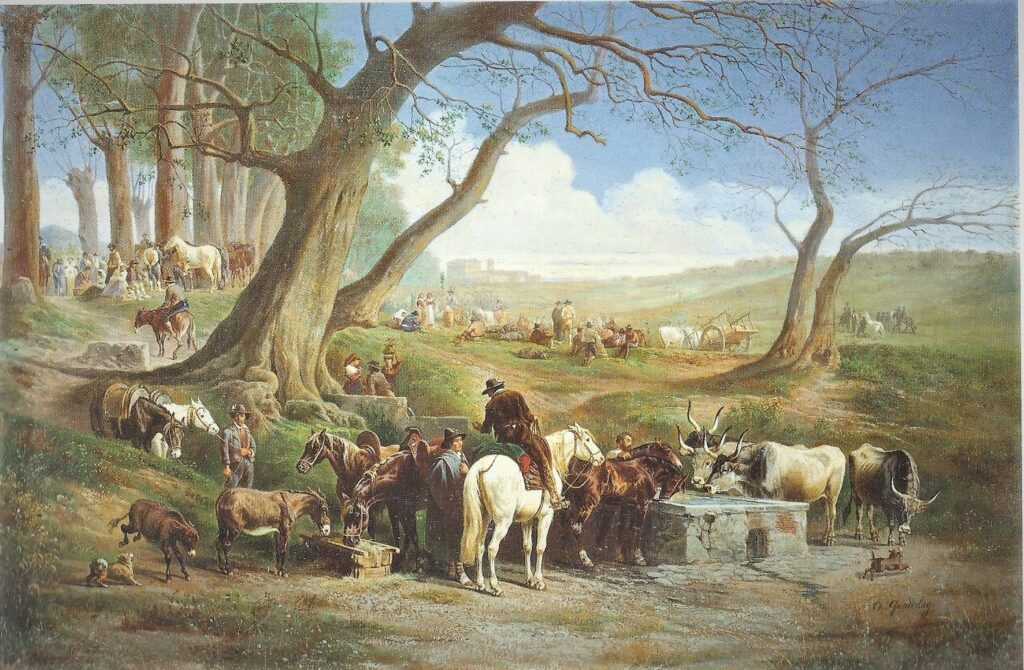

Quaedvlieg’s landscapes can be broadly categorized into rugged areas with buffalo herders or horse tamers, panoramic views with harvest scenes, and more intimate landscapes or animal studies. From around 1856, he began to specialize in depicting the landscapes around Rome.

These works clearly show the influence of English painters who had settled permanently in Rome. An essential difference from his earlier landscapes is the strong focus on the unity of humans, animals, and nature. He portrayed hard-working rural people and the untamed power of water buffalo and wild horses.

By the mid-19th century, haymaking and grain threshing became popular motifs in Rome. These paintings often depicted poorly paid day laborers and their families, living temporarily in primitive huts, tents, or even ancient tombs. Threshing, before the introduction of steam threshers, was done by horses driven in circles by a herder over an improvised threshing floor. At least six variants of such scenes by Charles are known today, showing both his working method and technical development. To prepare studies for such motifs, painters would often go on adventurous expeditions through scarcely inhabited areas.

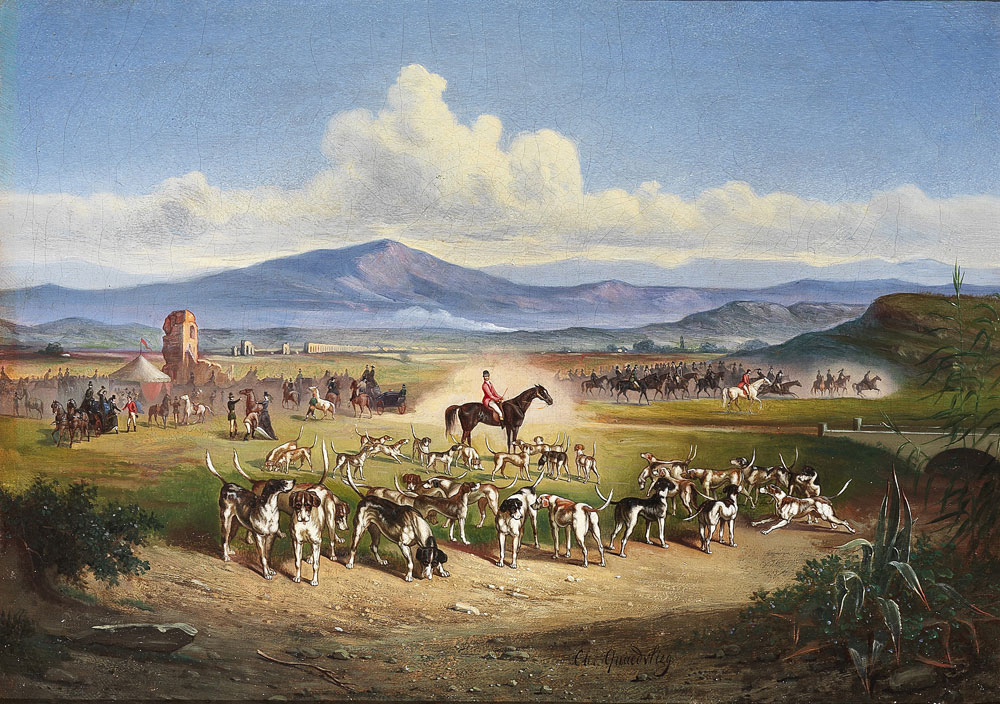

FOX HUNT WITH FRANCIS II AND “SISI”

Fox hunting, a typically English sport, was introduced to Rome in 1839 by an English lord. It was not hunting in the literal sense, but rather a skill-based social sport. In 1869, it took on the form of a “country club” with the founding of the Circolo della Caccia Roma, consisting of aristocrats and large landowners.

Quaedvlieg’s well-known paintings of the event trace back to the lavish Meet of 1870, held during the baptism of the daughter of the Neapolitan royal couple, Francis II of Naples and his wife Maria of Bavaria. Quaedvlieg is said to have been friends with Francis, who had been living in exile in Rome since 1860, and to have painted his portrait. Maria’s sister, Elisabeth of Austria (better known as “Sisi”), was also present. She is likely the slender, black-clad horsewoman in the foreground. Quaedvlieg often depicted individual scenes such as greetings, giving the paintings a narrative quality.

FINANCIAL PROBLEMS

After the unification of Italy in 1870, Charles’s financial situation appears to have worsened. Rome, now appointed the capital, was rapidly modernizing. The wealthy increasingly preferred extended stays in resort cities such as Venice. Meanwhile, new artistic trends such as plein-air painting, Symbolism, and Impressionism became fashionable, while Charles’s meticulous style went out of fashion.

In 1870, his works were still exhibited at a show personally opened by the Pope, featuring only Catholic artists. One such painting, The Blessing of the Draft Animals on St. Anthony’s Day (current location unknown), was sent to a Californian exhibition shortly before Charles’s death, likely to attract potential buyers.

AS POOR AS A CHURCH MOUSE

astor Welters notes that the remains of “Cavaliere” Quaedvlieg found their final resting place in a mass grave at the famous Campo Verano cemetery. Although an obituary in Le Courier de la Meuse (09 March 1874) mentions “a short illness” and “the administration of the last oil,” there are reasons to doubt the accuracy of this report.

The death certificate, drawn up by the Civil Registry in Rome (Ufficio di Stato Civile della Regione Pantheon), does not state the cause of death, as was customary. Musicians and a café owner were summoned to identify the remains of the painter from Valkenburg. He apparently died in solitude. Where were his wife, the priest, and his artist friends? Apparently, no one paid for a proper grave with a monument. What happened to the contents of his studio, including studies, sketchbooks, and letters?

Charles Quaedvlieg’s career ended much as described in Henry James’s novel of failure Roderick Hudson (1875): “If I hadn’t come to Rome I shouldn’t have risen, and if I hadn’t risen I shouldn’t have fallen.”

Michiel J. Roding Maastricht, January 2023